|

|

|

Niagara Falls

Friday, May 14 2010

location: rural Hurley Township, Ulster County, NY

This weekend Gretchen and I would be driving to Buffalo, NY to attend a party celebrating the marriage of our friends Doug and Felicia (whom we visited late this summer in Philadelphia). Similar to the way we'd handled our marriage, the marriage itself would be attended by a tiny subgroup of friends, and a larger group (including us) would be attending the post-marriage party.

New York is, it turns out, a large sprawling state, particularly by East Coast standards. Driving to Buffalo in our own state would be like driving to Staunton, Virginia. Gretchen had already devised a way for us to break the trip into two roughly-equal halves, which would involve lunch at a vegan café in Syracuse. Also, we wouldn't actually be going to Buffalo on the first day. We'd be going to the Canadian half of Niagara Falls.

Gretchen had never taken I-90 west from Albany (although once, after Ray and Nancy's wedding, we'd come east from Syracuse on I-90). I'd been this way once before that, back in the Fall of 1989 when attending a rare East Coast Earth First! rendezvous in the western Adirondacks, an unfunded mandate from my father back when travel meant hitchhiking.

I-90 west of Albany is unusually beautiful for an East Coast interstate. The Mohawk Valley is wide, low, and lush, but for some reason I-90 feels the need to stick to the highlands, where one has gorgeous views of quaint 19th Century factory towns such as Canajoharie. From the interstate, these places look like dioramas depicting an idealized vision of the early industrial age.

Out midway lunch stop in Syracuse was at a place called the Strong Hearts Café. One the chalkboard above the kitchen was a list of the vegan milkshakes, and they'd all been named after leftist icons from Chez Guevara to Elizabeth Stanton to Malcom X. I ordered a bowl of the corn chowder and sandwich featuring seitan and portobello mushrooms, and it was all delicious. Interestingly, we (well, actually Gretchen) kept having random friendly conversations with various people in the place, including a woman who had shown us how to use the complicated computerized parking meter out on the street. The sentiment we took away from this was "people in Syracuse sure are friendly."

Crossing into Canada was easy. The Canadian border guard was no-nonsense in his questioning, but he didn't notice or didn't care that that Gretchen's passport had expired in February. The fact that he didn't crack a joke, make a terrible pun, or say anything friendly was, in the spectrum of possibilities when dealing with Canadian bureacracy, akin to being sent to Guantanamo. But whatever, he waved us through. So then we were in Ontario, free to drive wherever we wanted in the second largest nation (in terms of geographical extent) on Planet Earth.

We found our hotel, the Rodeway Inn, and then moved our stuff upstairs. It was a nice place, with a king-sized bed, four (yes, only four) channels on the teevee, and a tub in the bathroom. As we were checking in, a group of young men showed up carrying a shitload of booze. They had to sign some sort of release, which, it seemed, is only required of bachelor's parties.

Gretchen and I walked down to the falls. Well, we would have had there been stairs available. But there were no stairs, so we were forced to use an incline that cost an absurd amount of money for carrying us the distance of five or six flights of stairs.

On the Ontario side of the Niagara River, there's a building facing the Horsehoe Falls, and it's basically a multi-tiered exposition all that anyone with taste has a problem with in North America. (I have to say North America, because, at this point, we were outside the crappiness familiar to anyone from the United States.) As we walked into the building, we found ourselves facing an enormous plushy beaver, and there at the base of it someone was posing for a photograph. They didn't look like they were posing ironically, but if they had they might have been making air quotes on either side of their presence in the photo. This was what Gretchen and I resorted to doing on the many occasions that followed when we were made to stand in front of a green background for a photo so later, when we emerged from an activity, the photo would be waiting for us with various views of the falls swapped in for the green. First, though, we went and stood at the edge of the falls, at an observation area that had been built into the cliff face at the Ontario end of Horsehoe Falls (43.07917N, 79.078136W). It was at that point that it became perfectly clear why we had come to Canada to see the falls. From our vantage point, the curve of Horsehoe Falls seemed to face us directly, just as a theatre faces a stage. But from any vantage point across the Niagara River on the New York side, the falls could only be viewed from the side.

Here above the falls, the clouds of mist rising from the roaring water could barely reach us, and only occasionally did it. The sun was behind us and a marvelous rainbow formed a nearly-complete arch. Everyone had their cameras out, and as with any beautiful natural spectacle, it seemed that a majority of those present to view it were various kinds of East Asians. If one looked over the edge, one could see a concrete pad down at the base of the falls, just beyond the deluge, where people outfitted with disposable yellow plastic raincoats marveled in the constant spray. That was where we went next.

To get down there, one pays a fee, gets photographed in front of a green screen, and then descends in an elevator to a series of tunnels in the cliff. Some of these tunnels emerge behind the falls, but there was nothing much to see there except a grey curtain of raging water. The view from that concrete pad was better, although the constant spray was unpleasant. Also, as someone would point out to us later, that water was the runoff from much of the entire North American superfund belt, including the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, famous for having caught on fire.

Gretchen seemed to be enjoying it all, but later she would make the observation that the informational plaques featured almost no scientific information about the geology of the falls. And a plaque about "stunting" (riding a barrel over the falls) was about as much history as was offered.

By the time we left the falls, we were eager to get out of what now seemed like a overly-commercialized dystopia. The building had been designed like a maze in hopes of increased retail opportunities from lost, semi-imprisoned tourists. It wasn't easy to extricate ourselves, but eventually somehow we got out and rode the incline out of the valley, ending up back on the streets of Niagara Falls.

Happily the iMax theatre was showing the movie about extreme sports, so we skipped that and went to the Skylon Tower, a sort of Seattle Space Needle as realized, perhaps, in the Soviet Union of the 1970s. From the ground it looked semi-derelict, like an artifact left by a long-extinct population of space aliens. We entered the wrong level inside its base, encountering a nearly vacant floor which continued the creepy Soviet Space Alien illusion. But then we bought our expensive tickets for the ride to the rotating restaurant at the top, hoping we could just get drinks and some French fries.

Before braving the rotating dining room, we walked around the caged-in outside of the tower, looking down first at the falls and then at the city to the west. The falls looked a bit insubstantial from this height, and Gretchen admitted that she was now finding them a bit underwhelming.

We'd been looking for evidence that something was rotating on the tower but weren't seeing anything. But then as we stood near one of the food stations, we saw that the dining area was moving with respect to the core of the building at a slow but noticeable rate. The place where the moving part of the dining area met the stationary part in the center was a thin seam in the floor, and at this point the divergence was happening at the rate of about a half inch per second. You could stand athwart the fault and gradually your legs would be pulled in two different directions. But it was all so smooth and gradual that waiters and other staff could walk back and forth across it without fear of stumbling.

It turned out that the crazy rules of the Skylon restaurant were such that we could get just drinks but if we wanted any food we would have to pay an $80 minimum. Since the restaurant didn't really have any food suitable for vegans other than French fries, that didn't seem like a wise financial decision. So we got back in the elevator and returned to street level. On the way down Gretchen asked the elevator guy what he thought of a Indian restaurant we'd seen on the drive in, and he pooh-poohed it as a "buffet place." Gretchen's revelation that we don't eat meat, not even fish, nearly made his head explode. Niagara Falls was seeming more and more as if it was stuck in some kind of time warp, a time when people still mostly just ate steak, overcooked carrots, and bland globs of mashed potatoes.

The Indian restaurant was called "Passage to India," and they did indeed have a buffet. And there was enough vegan stuff in the buffet for us to decide to go with it. We ended up having a pleasant and perfectly adequate meal. Gretchen seemed to think it was exceptional. Supporting this view, there was mango pickle in the condiments section, which Gretchen (who doesn't eat mango pickle, though I do) had never seen before. Most interesting of all was that our waiter was just some young white guy. You'd never see such a person working in an Indian restaurant in the United States, and it made me wonder if the rules in Canada are such that it is harder to employ members of your own family for shit wages.

After dinner, we went for a stroll and found our way into wandered into the Niagara Fallsview Casino Resort, a big fancy gambling establishment built around a huge fake hydropower generator that doubled as a water feature. After taking the elevator to the top floor to see what the view was like (there was none of the falls from the hallway), we went into the casino proper in hopes of maybe playing a nickel slot machine. But the machines only accepted Canadian currency or credit cards, and we didn't have any of the former and were pretty sure we wouldn't be putting a credit card in a machine designed to extract money from it. It was like a bad acid trip in there, with gloomy people and jarring dissonant sound effects from all the blinking and whirring machines. Watching Americans grimly throwing away their money is sad, but for some reason it's even sadder to watch Canadians do it. "There aren't many Asians here," Gretchen observed. "Yeah," I agreed, "they're too good at math." (Everyone's a little bit racist.)

Casinos are deliberately designed to be tractless mazes, self-contained civilizations where people bring their money so it can die. We had to ask directions to get out of there.

We ended up drinking wine at Zappi's, a pizza place next door to our hotel. The service was terrible and disorganized, but they had free WiFi. It was one of the few "free" things that can be had in a city designed from the ground up to nickel and dime. Unfortunately, we couldn't just buy a bottle of wine from the pizza place and carry it across the parking lot to our hotel, and there didn't seem to be any retail establishments designed to sell anything besides stuffed animals, refrigerator magnets, and coffee mugs.

View of Eleanor and Clarence the cat as we're leaving for the weekend.

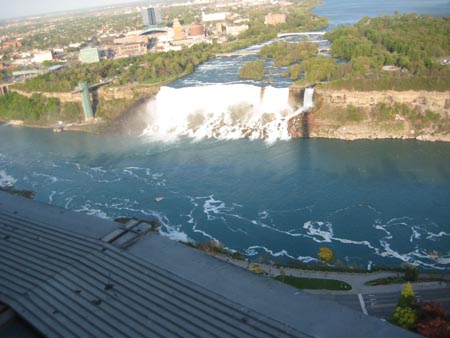

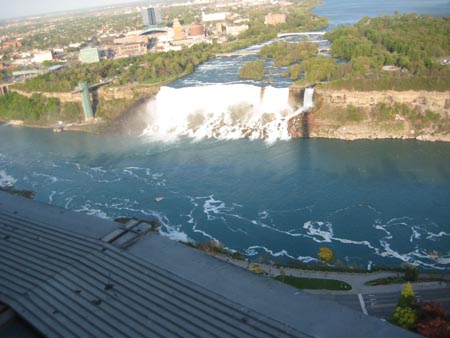

A view of the Journey Behind the Falls tourist trap building from above the incline.

A rainbow and the American Falls as viewed from the Journey Behind the Falls building.

People in the mist at the base of the Horshoe Falls.

Horseshoe Falls viewed from its base.

A rainbow at the base of the falls.

The Skylon Tower.

Horshoe Falls from the Skylon Tower.

American Falls from the Skylon Tower.

For linking purposes this article's URL is:

http://asecular.com/blog.php?100514 feedback

previous | next |