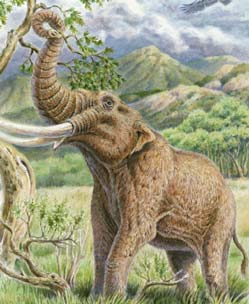

Megafauna: Mastodon.

Floral legacy: Cratægus.

Back to Forests of the Central Appalachians |

Feedback

The

following article was first published in the 1990 volume 10, number

3, p 23 of Earth First!

All

is concentered in a life intense

- Byron

Floral Legacies of the Megafauna

R. F. Mueller

Where

not a beam, nor air nor leaf is

Lost

Wander from the sea coast to the Appalachian crest - indeed almost anywhere in the Eastern US - and you will meet a familiar tribe - the hawthorns. Although most concentrated in Eastern North America, with more than 100 species, the genus Crataegus is found throughout the north temperate zone and many mountain ranges in the southern part of the continent. Small trees, or frequently only brush - sized, the hawthorns catch our eye with their hedge - shaped arboreal forms, heavy autumn crops of conspicuously - colored fruit and, above all, their formidable armament of long, sharp thorns.

The thorns of hawthorns are clearly intended to fend off browsers, who find both leaves and fruit highly desirable. Other plants in the rose family, of which the hawthorn genus is a member, are similarly desired. But what do the thorns fend off? Almost the only native browser in the Eastern United States in modern times, and for that matter during the entire Holocene Epoch, is and was the White - tailed Deer. The only other browser, the Moose, was confined to northern bog areas, and though Elk and Bison were present in the historical period, they are primarily grazers. Smaller browsers such as deer and domestic goats, are not stopped by large thorns, since they easily reach between them. These thorns, which in Cockspur Hawthorn (Crataegus crus - galli) reach 5 inches in length, were evolved to protect the plant from large browsers.

To find these large browsers we must look in the fossil record, back 12,000 - 15,000 years during the late Pleistocene, when an impressive megafauna ranged the land. According to John Guilday (Quaternary Extinctions, A Prehistoric Revolution, Paul S. Martin and Richard G. Klein editors, U of AZ Press, 1984) these large browsers included the Mastodon (Mamut americanum), Jefferson Ground Sloth (Megalonyx jeffersoni), Harlans Ground Sloth ( Glossotherium harlani) and the Stag Moose (Cevalces scotti). In addition two mammoths (Mamuthus) and a horse (Equs complicatus) probably browsed some. Other browsers larger than the White - tail included a tapir, a large peccary, and Caribou.

The browsing habits of these larger animals must have been quite different from those of the delicate - muzzled deer. It seems likely that they would have broken off whole branches or engulfed entire branch ends, stripping off the leaves and small twigs, as existing elephants do. Feeding leaf by leaf as deer and goats do would not have satisfied their enormous intake requirements. With these aggressive browsers the long thorns would have been the perfect counterpoise to maintain a balance between the eaters and the eaten. The hawthorns even went so far as to protect themselves from possible assaults on their nutritious inner bark by evolving "monkey puzzles" of large complex thorn growths on their trunks.

If thorns were so effective in deterring browsers, why didn't more of the hundreds of other tree species in North America evolve them? The answer to this is complex and probably will never be completely known. However, as indicated previously, many members of the rose family seem to be particularly attractive to browsers. Also, it is likely that many other species found it more economical to invest their energy and nutrients in chemical defenses.

Several other members of the rose family do have thorns for defense. An example is the Wild Crab Apple (Pyrus coronaria ), which is almost as well defended as the hawthorns. Another is the Wild Plum, though its thorns are less impressive. Additionally, thorns are prevalent in the legume family. In the Eastern US the thorny legumes include the Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) and the Honey Locust (Gleditsia tricanthos). The latter has impressive thorns on both branches and trunk.

Another factor governing the development of thorn protection is habitat. Evidence indicates that, by and large, the megafauna occupied open savannas and spruce - pine - shrub parkland rather than deep forests. This open country would probably also have been the preferred location for hawthorns, crab apples, plums and locusts because all are intolerant of shade and today are more at home in forest edges and clearings than in deep woods. At present we can see hawthorns flourishing in openings of montane Red Spruce forests of the high Alleghenies, a habitat that approaches that inferred for the Pleistocene mastodon. Species of maple, oak and other components of the great mixed deciduous forest would have been exposed to heavy browsing only at forest edges since forest interior habitat would not have been favored by the megafauna. Finally, many plants may not have adequate genetic resources to evolve them.

Clearly, the hawthorns, Honey Locust and other heavily - thorned plants are relics of another time and most significantly of a fauna long vanished. This fauna became extinct approximately 10,000 - 11,000 years ago, a time span apparently sufficiently short for the thorns to persist. There simply have not been enough generations of trees since the Pleistocene to breed out a feature so beneficial when large browsers were around. Also, there is probably some residual benefit in the thorns, since they do slow even small browsers. However, the thorns represent a considerable investment in energy and nutrients, and one would expect them to gradually disappear or be replaced by smaller thorns.

Very likely, thorns are not the only persisting relics of the megafauna. They are simply the most visible. There may be a host of chemical repellants that are specific for mastodon, ground sloth and other megafaunal browsing niches and have not yet vanished. The same may be said of fruit and seeds designed to be dispersed by the megafauna. An example of a fruit may be that of the thorn - bearing Osage Orange ( Maclura pomifera), which is at present consumed by horses but not by cattle, and would probably have also appealed to Pleistocene horses and other megafauna (Gus Mueller, personal communication). Even form and growth habits of trees and bushes were probably sensitive to influences of the great browsers.

The thorn plants we see today are graphic reminders of how much the planet has lost since the Pleistocene. They are messengers from the grand age of wilderness that for some unknown reason underwent a transformation at the beginning of the Holocene, but still retained its ecological integrity until European man began to destroy it. The megafaunal browsers can be regarded as predators of a type, albeit of plants. Like their legacy of thorny plants, existing ecosystems are part of the preexisting complex of predator - prey relationships. Although the most important large predators of the Holocene have been extirpated in the Eastern US, the "ghosts" of these predators haunt us by the wild characteristics we so admire in their remaining prey fauna - the fleetness of the deer and the craftiness and stealth of smaller herbivores and carnivores that were hunted by them. The absence of the large carnivores has thrown these ecosystems out of balance. The small carnivores, the Raccoon, the Opossum, skunks and foxes, have increased in numbers to where they contribute significantly to the decline of many birds and other prey. Also, it is likely that some endemic plants have been brought to extinction by the over abundant deer which leave high browse lines on trees in many areas. The sum of these effects is genetic deterioration, loss of species diversity and general environmental degradation. What began as perhaps a "normal" ecosystem transformation at the end of the Pleistocene has turned to pervasive decline heading toward collapse.

We can't bring back the thorn - molding megafauna, but we can and must bring back the assemblage of Wolves, Panthers, Wolverines and large raptorial birds that form the peak of the trophic pyramid and are needed to balance the system. We must also try to bring back the large ungulates, the Elk and Bison, to reclaim their important niches. More than an atavistic wish, this restoration of the rightful heirs to the land is an ecological imperative that is gaining credence with each passing day as our dependence on nature and ecosystems becomes more evident.

R. F. Mueller is a former NASA scientist and [ former] Virginia EF! contact.

Floral legacy: Cratægus.

Back to Forests of the Central Appalachians |

Feedback