|

|

|

Waltham, Massachussetts

Sunday, November 2 2003

Today was my father's 80th birthday (for those who have forgotten basic arithmetic: he was born in 1923). Gretchen and I called him from the Massachusetts Turnpike today to wish him a happy birthday. He said he'd been splitting wood this morning. It's rare that I talk to him on the phone and he doesn't tell me he'd been splitting wood just that morning.

Gretchen and I were headed to Waltham (outside of Boston) to attend an "Open Studios" at the Waltham Mills Artists' Association. It consists of several large old warehouse buildings that have been converted into artist studios. Many of the artists actually live in their studios, though I get the feeling this isn't officially sanctioned.

We arrived at the studios at around 12:30pm and went directly to the studio of the artist who had told us about this event, Johnny C. Johnny shares his studio with his wife Carol, who is a photographer. I've seen Johnny and Carol at a couple weddings, particularly my own. Johnny and Gretchen were off-campus housemates while they were students at Oberlin. Johnny's work is centered around the traditional making of books - usually several-of-a-kind art pieces made with clever time-honored printing techniques and elaborate bindings. Most people never stop to consider how a book is physically created. Johnny C. has mastered that process and, as evidence of his virtuosity, knows how to break all the rules.

I was particularly interested in a large black machine commanding one corner of Johnny's supremely cluttered studio. It was a 1930s-era Linotype, taking up the volume of two refrigerators but shaped like the descendant of several generations of mechanical miscegenation involving bicycles, manual typewriters, sewing machines, and an oil furnace. Back in the 1930s, a Linotype's level of automation must have seemed almost magical. Typing on a keyboard automatically adds the molds for individual letter presses to a line of such presses. As this is done, the presses line up in a special display area where the typist can read the composed line on the backs of each letter mold. After a special button is pressed, the line is whisked away and used to mold a lead slug capable of printing that line of text in a press. This part of the process involves a crucible of molten lead. After the line is formed, the individual letter molds are dropped into a hopper and sorted according to encoded tabs on one end so that they can go back to their respective place in the magazine (just like a gun magazine) to be used again in molding the letters of future lines. It's a wickedly ingenious device, with evidence in its construction of layers and layers of innovation. These days innovations to similar devices can be done simply by editing text files. With the Linotype, it's all about gears, levers, and good lubrication. Perhaps the most amazing thing of all is that this Linotype was a functioning machines, used routinely by Johnny C. in his print shop. To keep it in operation, Johnny has to know how it works in detail. It's doubtful he has access to anyone who can fix it any better than he can. Near the Linotype was a well-thumbed handbook detailing its maintenance, operation, and repair.

In addition to various "art books" Johnny had a number of posters that he'd made using a set of illustrative wood blocks from a 19th Century issue of Webster's Dictionary.

Johnny's studio is actually called the Quercu$ Pre$$ and seems to employ a few people in addition Johnny himself. One of these was a young Oberlin graduate named Tonya whose job was to accost visitors and make them print something on one of the smaller hand-operated presses.

[REDACTED]

Eventually Gretchen and I went off and wandered around in the other studios of Waltham Mills. I could go on at length about what was good and what wasn't, but it hardly matters. It was your usual art walk type experience, which is sort of like walking around in a museum of unfamous works. The big difference, though, is that in an art walk of this sort, one's blood sugar never ebbs away because it is continually being replenished. Most studios had carbohydrate-rich food available, and some even had wine. One of the most amusing things about the entire experience was the availability of pretzels - nearly every studio had a jar of them. Some were of the curvy figure-eight variety, and others were various versions of the ever-popular "edible cigar." Here at Waltham Mills, the pretzel was sort of the minimum refreshment provided. After a dozen studios or so, we made a game of identifying the pretzels before even looking at the art.

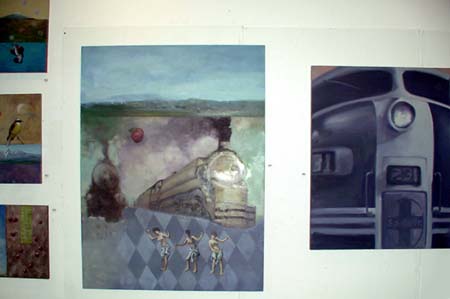

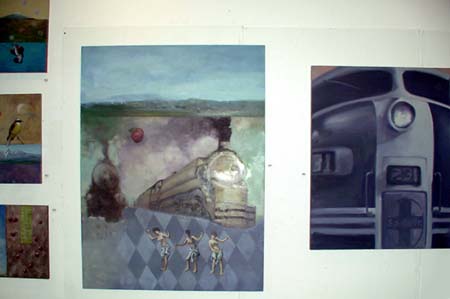

Gretchen and I had liked the works of Michæl B. Wilson, and after fussing over Wilson's necktie-wearing dog Oliver, she bought one of his prints. He seemed to have a fondness for the fronts of diesel trains and portraits of flowers and birds against abstract backgrounds of indeterminate depth.

Some time later we were in another studio belonging to Stacey Cushner and saw that some of her works were compositionally very similar (see photo below). There obviously was some common origin for such similarities, whether it was influence, an art class taken together, or the intimate milieu of the community. Gretchen asked Cushner about the similarities, and she seemed miffed to have it brought up.

We sat for a time sharing a beer (well, I was the one drinking it mostly) and watching a trombone quartet in the cozy studio of Jonathon Nix, surrounded by his lush hyper-saturated oil paintings, many of them containing Hebrew characters and human figures. Nix was in an impatient mood and asked the trombonists at one point, "When can I have my studio back?"

Back in Johnny's building Gretchen and I watched a series of handmade short films, the most interesting of which was called "Abandoned Insane" and mostly consisted of stop-action frames photographed at an abandoned mental institution. The frames included numerous dead skeletonized pigeons.

Later on a large group of us went out together for pizza, wine, salad, and beer at a nearby place called Brickoven Pizza. Dinner conversation was interesting and often very funny. I'm glad I was seated directly across from Johnny C. (even though this meant I had to sit near his baby as well) - he's an entertaining guy.

Gretchen and I drove back home tonight after dinner, forgoing a plan to possibly stay with Nina and Karsten in Amherst. (Nina is a mutual friend of Johnny and Gretchen, though I don't think she likes me very much.) As we were leaving Waltham, Gretchen insisted on driving, saying I'd drunk way too much wine and beer. I wasn't the slightest bit drunk, but I agreed with her, saying things like, "If I need to throw up, just pull over, okay?" and "I'll be very surprised if I can remember this moment tomorrow."

One interesting thing I noticed from this day spent in a Boston suburb was that I never once heard a Boston accent. All the people I'd heard speaking, both artists and art buyers, had either been from elsewhere or had been aculturated in such a way (think television and education) that they had lost their accent. This isn't uncommon; I grew up in Redneckistan between the ages of seven and eighteen, yet I'm told my accent, if anything, is upper Midwestern (with occasional influences from both Appalachia and New England).

The bridge across the Hudson River on the way from the NY Thruway to the Mass Turnpike.

Johnny's vintage 1930-era Linotype machine.

The keyboard of the Linotype.

The lead crucible in the Linotype machine.

Clutter in Johnny's studio.

Clutter in the kitchen.

Tidy and religious wall groupings in another studio.

Some paintings by Michæl B. Wilson, whose works we liked. Click to enlarge.

A train by Michæl B. Wilson. As someone with experience in the process of painting, I thought I had a good idea of how this one came to be. Wilson had painted a train, decided he didn't like it much, and put down some transparent layers of blue over it. Then he completed it with a simple flower - not having known from the start that it would end up that way. Whether or not this was his actual process, I cannot be sure.

Michæl B. Wilson's dog Oliver.

From left: Gretchen, Nina, and Karsten in Michæl B. Wilson's studio.

We found several paintings by another artist named Stacey Cushner which were strangely similar to the ones we'd seen by Michæl B. Wilson. Here you see one of Stacey's prints (left) next to one of Michæl's that Gretchen bought (right).

Me in a bathroom.

For linking purposes this article's URL is:

http://asecular.com/blog.php?031102 feedback

previous | next |