|

|

|

walls of Jerusalem

Sunday, October 2 2005

setting: Eldon Hotel, David Ha-Melekh Street, Jerusalem, Isræl

The breakfast at the Jerusalem Eldon is a riot of deliciousness. Unfortunately, we woke up a little too late to get the entire experience.

We walked across West Jerusalem to the indoor Mahane Yehuda market, referred to by Gretchen mostly using the Arab word for such markets, "the Shouck." It's a frequent target of suicide bombers so I was a little creeped out by the place despite the exhuberant capitalism, colorful piles of produce, and "if these walls could talk" ambience. Gretchen recognized a tall guy immediately as Danny B!ernbaum, a fellow classmate from Oberlin, so we spent the rest of our time at the market with him as he went about his shopping. These days he's a "modern orthodox," meaning he wears a kippah and observes all the rituals, but he's still connected to (and not repulsed) by secular society. He lives alone and would be interested in dating, so this of course launched Gretchen into one of her happier roles, that of matchmaker. Of course, since Gretchen doesn't live in Isræl, this meant she'd have to work through a proxy, in this case Dina.

The Shouck is not always a pleasant place for an animal rights nut like Gretchen. Happily, though, she missed the scene where the shopkeeper clunked various live fish on their heads before quickly deboning them and throwing their flesh into a grinder to make Danny his gefilte fish.

This afternoon the plan was to meet Dina and Gilad at David's Tower inside Jerusalem's walled Old City and then walk around the various quarters (of which, unlike those ounces of pot you sold back in college, there are only four). We were running a little low on time and arrived at the tower late, but Dina (as usual) was running even later.

The Old City, at least as approached from the west at the Jaffa Gate, is strictly medieval in character. It comes as no surpise, then, that it dates to medieval times. As for nearby David's Tower, the name is a misattribution, a common thing in a city where everyone wants to associate with or coöpt something ancient and holy.

I noticed that immediately across the street from David's Tower was the office for the local branch of Jews For Jesus. I could see faintly beneath layers of white paint that a sign now reading "GOD IS LOVE" once read the far more controversial "JESUS DIED FOR YOUR SINS. HE HAS RISEN. PLEASE COME IN." Christianity has generally been an easy sell wherever it's been prosyletized (it's certainly easier than, say, praying five times a day and fasting for a month each year), but Jews can be tough customers.

After Dina and Gilad arrived, we dove immediately into the Armenian Quarter, or at least a shop-lined stretch thereof. It was like a one-dimensional version of the Souck and looked as ancient, though every dozen feet or so down the flagstone walkway there'd be a steel sewer lid cover, indicating some changes had been made since medieval times. In some cases, though, these changes were to revive the ancient, as opposed to just immitate it. Some of the flagstones we were walking on had been unearthed during the sewer project and been recycled.

The sewer lines continued into the Muslim Quarter, but otherwise it had been left largely the way it had always been. In general the Arabs are suspicious of any activities in their neighborhoods undertaken by the Isræli government and, to minimize tension, Isræl doesn't meddle with these Arab places any more than it feels it absolutely needs to, and this lack of meddling tends to preserve the character (or, if you prefer, funk) of the place.

We ended up at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The first thing that one learns about this, the holiest of holies for Christiandom, is that it is frozen in the amber of status quo. Conflicting Christian sects have conflicting beliefs and claims throughout the church and have historically been unable to agree on how the place should be run or who should do what, so they've observed a policy of doing things exactly as they were done in 1852 when the Turks decreed that this would be the policy. A ladder on a second-floor balcony above the main entrance has been there since the 19th Century and certain steps are swept by representatives of one sect while adjacent steps are swept by those of another. For some things related to the church, it's best to rely on disinterested non-Christians. For example, the keys to the church are held by a Muslim family that has served as the key holder for generations. These conflicts, and the way they've been addressed, are a microcosm of the problem of Isræl itself, a land holy to three religions and claimed by two conflicting ethnic groups. These conflicts are stronger with regard to Jerusalem, the geographic homunculus of Isræl, and stronger still with regard to the Old City, the geographic homunclus of Jerusalem. The conflicts reach their peak with regard to the Temple Mount, the geographic homunculus at the very center of everything. Mercifully, though, the Temple Mount is claimed only by Jews and Muslims, not Christians. (There will be more about the Temple Mount a little later.)

From the courtyard in front of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre the building isn't especially impressive, especially given the grandeur of the Old City and its gates. The single entrance door isn't especially big, and once inside the place doesn't seem all that big. To appreciate most of the interior you have to have faith that real things happened to a real man-God here. Short of that, it can be a little awe-inspiring just to watch the reverence of people who really believe all the Jesus stories were true and that they all actually took place here. When there are no reverent Christians to watch, the graffiti and other ancient textures are worth exploring.

Gilad pointed out that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre differs from familiar western cathedrals in that it developed organically, without much or any planning. If someone needed a new chapel or decided that Jesus did something notable on a nearby piece of ground, they just built something and connected it to the rest of the building. These days, even under the policy of status quo, it's occasionally possible for new construction or rennovations to take place. Consequently, the interior is a patchwork of styles and ages. I saw ornate medieval doors within feet of the cheap luan variety one can pick up for $20 at your local Home Depot.

The one architectural marvel in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is the Rotunda and the curious Edicule, a small blackened building directly beneath it. It is from this spot where Jesus is said to have risen into heaven (this was how gods traveled back in those days).

From the Church of the Holy Sepulcre it's possible for the devout to follow the various actual stations of the cross, which seem to spill into what is now the Muslim Quarter. Not being either devout or Christian, we picked our way back to the Armenian Quarter and then into the Jewish Quarter. At this point it's important to note that the Old City of Jerusalem was isolated from Isræl between 1948 and 1967, when Jordan controlled that part of the city. During this time the Jewish Quarter was looted and many buildings, particularly synagogues, were destroyed. When Isræl took the Old City in 1967, the ruined Jewish Quarter provided an opportunity for both modernization and the preservation of certain ancient features. Thus, while in some places the Jewish Quarter takes the form of a tastefully upscale urban mall, in others the surface is stripped away to reveal Roman and Judean ruins and informative bilingual signs explain what it is you're seeing. The most spectacular of these displays is the remnant of the old city wall dating to 700 BC. A map explained how this wall had been Jerusalem's western wall back when it had been centered more to the east. At that time, the Temple Mount had been in the city's northwestern corner. Now, though, that same Temple Mount, holy as ever if not more so, is in the Old City's northeast corner.

After being successfully pressured by a Jewish Quarter merchant into patronizing his sidewalk café, I drank what was to be the most pathetic "Turkish coffee" in my life. Having not yet been to Turkey, though, I didn't know quite how pathetic.

Our next stop was the famous Western Wall (or "Wailing Wall"), the holiest site of Judaism short of the terrain occupied by the Muslims at the top of that wall, the Temple Mount. In general Jews are content with restricting their worship to the wall; among the religious there is actually concern that the Temple Mount is too sacred to be entered by Jews, at least until they can get the provisions necessary to properly sanctify themselves. These provisions include the ashes of a red heifer born in Isræl, ashes which do not currently exist but are in the works (thanks to the efforts of Christian fundamentalists who think it will speed the arrival of Armageddon and the End of Days).

The first thing you see when you emerge from the twisting streets of the Jewish Quarter on the crest of a low hill is the gilded spectacle of the Dome of the Rock, the third holiest shrine in all of Islam and supposedly the place where several important things happened: the gathering of clay for the making of Adam, Abraham's near-sacrifice of his son Ishmæl (not Isaac, Muslims insist), and the ascent of Muhammad into heaven. To its right (and south) is the brooding and decidedly less spectacular Al Aqsa Mosque. Both buildings sit on a rectangular mound held in place by ancient stone retaining walls made of massive cubic stones. Supposedly these stones couldn't be sundered even by an army of pissed-off Roman engineers intent on destroying the Second Temple of the Jews. The face of the wall one sees from the Jewish Quarter is the Western Wall, and these days it marks the eastern limits of a broad, sloping plaza paved with familiar cream-colored Jerusalem limestone. Gildad told us that until 1967 this plaza had been cluttered with houses, shops, and twisting streets like the rest of the Old City, but all of these had been demolished to open up the Wall and make it a better place for worship. Previously, before Jordanian occupation in 1948, it had been accessible as the cramped terminus of a blind alley, but it was completely inaccessible to Jews between 1948 and 1967. (Gretchen tells me that there is a famous photograph of Isræli soldiers reverently standing at the wall after 20 years of doing without.) What Gilad didn't tell us was that the houses and shops that had once occupied this broad plaza had once comprised a fifth quarter of the Old City, the so-called Moroccan Quarter. It was demolished by the Isræli government after only two hours notice to its 650 residents.

On this particular day, the plaza was full of several different large groups of Isræli soldiers, most of them segregated by gender. The Wall is the spiritual center for Isræl and makes its own unspoken nationalist argument. Bringing troops here for various ceremonies gives them common cause and provides the argument for why they are obligated to serve.

Not being Jewish, I was actually a little underwhelmed by the wall. I expected it to be taller and wider and I sort of wanted to feel something spiritual somehow. These holy sites derive their power from the placebo effect of faith, and without that they are merely piles of stone. I'm a little jealous of people who have faith in Gods and engage in various forms of magical thinking. They experience places like the Western Wall in a way that completely eludes me.

To get to the plaza near the Wall, one must pass through a metal detector. As one gets closer to the Wall, orthodox rules dictate that people must segregate according to gender. The men get the broadest expanse of the wall at the northern end, whereas women get a smaller piece to the south on the other side of a barricade, beneath a mysterious roofed wooden ramp leading to the top of the Temple Mount (who gets to go there?). Gretchen and I divided and went our separate ways to our respective genders' sections of the wall. As I put on a cardboard kippah out of respect for the purported holiness of the site, a Hasid came up to me asking if I wanted to put on Tefillin. He asked this in Hebrew and the only word I understood was "Tefillin." Of course I wasn't interested, and right away it was clear I couldn't speak Hebrew. "Are you Jewish?" he wanted to know. "No," I said. "Then why are you in Isræl?" "I came to a wedding. My wife is Jewish." I explained. He wished me a good visit and I walked up to the wall and pressed a finger to its shiny oft-touched surface. In the cracks between the stones were thousands of rolled-up pieces of paper with messages and prayers.

Back in the plaza we sat around watching the giddy young soldiers as they stood around chatting or were organized to perform half-hearted drills. Their machine guns had gaping rectangular holes where the curved bullet clips normally would have gone.

Eventually Dina and Gilads' respective families showed up, contributing to a general paralysis of decision. Originally there'd been a plan to tour a tunnel running along the base of the Western Wall further north, beneath the Muslim Quarter, or perhaps see the recently-exposed Southern Wall of the Temple Mount, but by now the day was getting a little too long in the tooth for such things.

At some point a woman came up to Dina's mother offering a shawl so she could cover her shoulders. Evidently the bare shoulders of a 60 year old woman is a tempting enough sight to profane the holiness of a 2000 year old wall, and this woman with the shawls makes it her business to keep that from happening. She didn't, however, seem the least bit concerned about cloaking the bare shoulders of a young male construction worker resting on the plaza.

We walked for a distance along the ramparts of the Old City as we were finding our way out. From here we could see the graveyard atop the Mount of Olives, where (supposedly) the first wave of resurrections will take place when Jesus returns. Off in the distance in a few places we could see the new wall being built by the Isræli government to separate Isræl and some of its illegal West Bank settlements from the riff raff and potential suicide bombers of the Arab West Bank. Jerusalem has always been a city of walls, so why stop now?

This evening we all went to the house in Jerusalem of one Dina and Gilad's friends for a little party thrown in honor of the bride and groom. (Such parties are a traditional part of a week-long Jewish wedding extravaganza.) It was a family-friendly affair, with several generations of relatives from families of both the bride and groom. There was plenty of alcohol, but since nearly everyone there was Jewish, everyone was eating and nobody was drinking. It's a stereotype, I know, but it's firmly grounded in fact.

There were a couple young modern-religious women at the party who Gretchen and Dina thought might be a good match for Danny B!ernbaum, Gretchen's Oberlin friend whom we'd me earlier in the Souck. But with a little questioning it soon became clear that one of these women already knew Danny and that wedding bells were not going to be ringing. Jerusalem may be a lot of things, but (somewhat surprisingly) one of them is a small town. In Jerusalem, if you're in a certain scene, chances are you know everyone else in that scene. It's more like Charlottesville than New York City.

Towards the end of the festivities, Gilad's ultra-orthodox brother-in-law stood up and said a few things, asking first if he should make his remarks in English or Hebrew. In English, then, he talked at some length about how when a man and woman get married, the whole is bigger than the sum of its parts. It was very Plato's Symposium and Gretchen found it very moving. But when he was done he gave Gilad an enthusiastic hug and then was careful not to touch Dina, since doing so is forbidden by the sages.

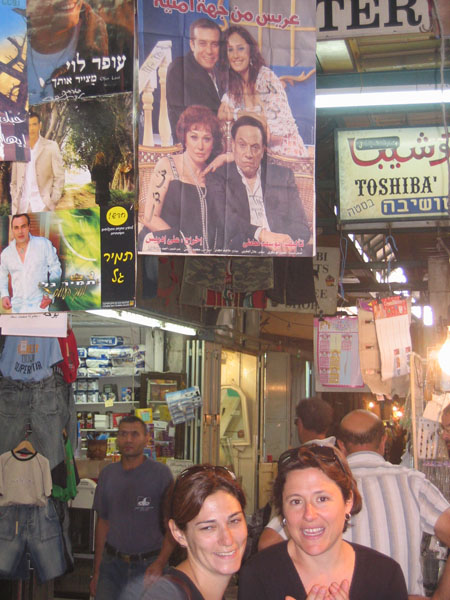

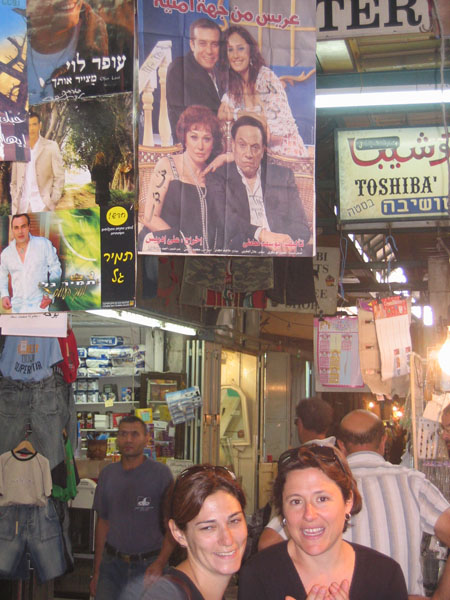

The Souck.

Gretchen with Danny B. in the Souck.

The kind of outdoor plumbing you can get away with where it never freezes hard.

The western wall and Jaffa Gate of the Old City.

Me and Gretchen at David's Tower.

Old City center for Jews for Jesus.

Look what turning up the contrast reveals.

The one entrance of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. You can barely see the ladder in the second story window that has been in the same place since the 1800s.

Graffiti in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Art in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

The dome through which Jesus ascended in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Me and Gretchen with Gilad in the Muslim Quarter.

Me and Dina at one of the Stations of the Cross.

Dina and Gretchen in or near the Muslim Quarter.

The Dome of the Rock atop the Temple Mount.

Soldiers and civilians in front of the Western Wall.

Closeup of the Western Wall.

The new separation wall between Isræl (foreground) and the Arab West Bank.

For linking purposes this article's URL is:

http://asecular.com/blog.php?051002 feedback

previous | next |