|

|

|

Petra

Thursday, October 6 2005

setting: Taybet Zaman Hotel, Taybet, Jordan

At 4:00am, before anyone could even distinguish a white goat's hair from a black one, the speakers on the minaret of the mosque above our hotel started up with the morning call to prayer. It was mercifully short (maybe two minutes) but it had an urgency about it that might have been the related to Ramadan. If Muslims didn't hurry up and eat their morning meal, they wouldn't be able to eat again until the break of fast at the end of the day (iftar).

The big activity today was a visit to what remains of Petra, the ancient capital of the Nabateans, a pre-Islamic Arab people who specialized in trade. Eventually subverted and then conquered by the Romans, the unique character of Petra was first Romanized, then Chistianized, then abandoned to grave robbers and bandits, who stripped it of anything valuable and hid out in the inaccessible nooks and crannies of its complex of natural sheer-walled gorges cut into solid sandstone. Petra was rediscovered in the 19th Century and has only recently developed into a tourist attraction, mostly the result of an Indian Jones sequel shot in front of its most spectacular tomb.

Modern Petra lies north of Taybet by ten or twelve miles. Along the way, the road leads past a peak with a white dot at its summit. This is, we were told, an Islamic shrine for Aaron, the brother of Moses.

Ancient Petra is a couple miles from the modern version, hidden away in a swath of what can only described as badlands. At the entrance to the archælogical site there are restrooms and plenty of vendors selling everything from coffee to carpets. The names of the shops sometimes have some relation to ancient Petra, for example, "The Indiana Jones Carpet Shop." More mysterious is "Titanic Coffee," featuring a huge picture of the famously ill-fated ship on its maiden voyage. I'd heard something about the Titanic brand craze, particularly in Afghanistan, where everyone wanted to associate their products with the extremely popular movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet. It was amusing to see this still going on outside ancient Petra all these years after the movie failed to have a sequel.

You enter the archælogical site of Petra via a quarter mile gravel road. There are horsemen at the top of this road and they desperately want you to accept their services for a horseback ride down. Since, according to our guide, our particular tour had already paid for horse rides, we did the horse thing. The guys with the horses were a rough and ready sort, and they had little patience for their animals even when they were doing exactly as instructed. Gretchen and I were in the lead, and initially the horsemen were just going to lead us down to the bottom, but when it seemed both of us knew how to ride (however marginally), they turned us loose, more or less. They still issued commands to the horses from a distance, and in general the horses obeyed. The command for "giddyup" was "sk-sk-sk" (a click made with the side of the tongue and roof of the mouth) and it was something I was familiar with from growing up with three horses and a horse-obsessed mother. More important to me was the command to stop, which was the completely unfamiliar "Shhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!" I had to be careful with that one, because the horse was capable of a very immediate stop, and I almost went over his shoulders the first time that command was issued. My horse was remarkably good at weighing the importance of various commands. Mine were given a very low priority, whereas the commands issued by his master, even from a considerable distance, were acted upon immediately. Once we were done with our rides, it was expected that we give the horsemen tips, a responsiblity we had to leave to Gretchen's father, since he was the only one carrying any money. The currency in Jordan is the Jordanian dinar, though American dollars are cheerfully accepted (even though they are worth somewhat less than dinars).

The place where the horseride ends is the site of a dam built by the ancient Nabateans to divert water and keep it from entering one of the gorges. Inside this now-dry gorge, a road was built, starting with an elegant arch that collapsed relatively recently (maybe 100 years ago). As you descend into down this roadway, you periodically see the various reliefs and sculptures that the Nabateans carved. Many of these were in homage to the three primary gods of their "triad" religious system, which bears an uncanny resemblence to the Christian notion of the Trinity. (This does a lot to explain why Christianity was adopted so quickly by people who had long resisted the pure monotheism of the Jews.) There is also a curious pantheon where Gods from several different religions could be addressed in one place, an early exercise in tolerance and the acceptance of diversity which, as our guide pointed out, was an essential character trait of people who made a living through trade.

I should stop here and mention a few things about today's guide. He was a huge upgrade from the one yesterday who had taken us through Wadi Rum. For one thing, he had studied abroad in several places and had not only mastered English, he was also conversant in Chinese! (If he could get a security clearance, there's probably a huge demand at the CIA for someone with conversational abilities in Arabic, English, and Chinese.) Gretchen latched onto him from the get-go and asked him question after question about Jordan particularly with regard to the rights of various minorities. She also wanted to know about Jordan's relationship with Isræl, Jews in general, and Palestians, many of whom fled to Jordan at the conclusion of the 1948 war. One of the earliest revelations that endeared our guide to Gretchen was that he too was an atheist and, furthermore, he didn't fast on Ramadan. (However, he said, in Jordan any healthy adult male who eats publicly during Ramadan risks prison time.)

In general, in response to Gretchen's questions, our guide made the case that Jordan has come a long way and stands head and shoulders above other Arab nations when it comes to democracy and human rights. Nonetheless, medievalist tendencies continue to permeate Jordan. When asked how gay people fair in Jordan, our guide was adamant, "There are no gay people in Jordan." "Come on," Gretchen said, "there are gay people everywhere." (Indeed, the guide himself had already set off my admittedly-inaccurate gaydar equipment.) According to our guide, being gay in Jordan is widely considered such a bad thing that no one would ever cop to it. "Then who fixes people's hair?" I interjected. This was one of the few contributions I made to the the multi-hour conversation.

A second surprising bit of continued tribal medievalism in Jordan is the persistence of honor killing, particularly of an unmarried daughter who gets pregnant and cannot convince the father to marry her. Goofy as this seems from a Western mindset, in Jordan, families still kill their daughters over this issue. A daughter's only way out in such a situation is to flee to a Bedouin camp and seek its leader's protection. Bedouin villages are still largely autonomous and no one would dare to take on a Bedouin chieftain even over a matter this supposedly grave.

Gretchen had asked yesterday's guide about the Isræl and Palestinians and she continued these questions with today's. Both had a generally negative view of Jordan's Palestinian refugee population, which actually constitutes a majority in Jordan, regarding them as having overstayed their welcome and still bitter about the attempted overthrow of the Hashemite Kingdom by Palestinian rebels in 1970. (At some point in this part of the dialogue, Gretchen's father took her aside and whispered that maybe she shouldn't be pushing the discussion in this direction, that it was a sensitive one for Jordanians. Supporting this assertion, I noticed that our guide generally kept his voice down as he talked about both the Palestinian situation and the continued existence of honor killings).

As for Isræl, though he expressed a desire that some solution be found for the Palestinian situation, our guide insisted that Jordanians have come to accept the existence of the Jewish state and want to remain on friendly terms with it. Furthermore, he added, the Isrælis have made valuable contributions to the field of desert agriculture, and Jordan has benefited from these. He was quick to mention drip irrigation, which everyone always does when the subject turns to Isræli agriculture.

One last tidbit about today's guide applies to other men we met in our Jordan adventure, including our main driver, a man whose first named was "Baker." They were all very proud of the fact that they had a certain amount of French ancestry, that is, that they had descended from Christian crusaders. They'd all been raised in Muslim families and identified themselves as Muslim at least in a cultural sense, but they seemed to be thrilled by the exoticness of the notion of tracing their lineage back to European knights. This is a little like white guys in the American south who beam with pride as they talk about their Cherokee grandmothers (though they'll rarely cop to having Cherokee grandfathers).

We continued down through the narrow gorge, the cliffs nearly closing overhead in some places. The ancient Nabateans were a cunning people, and they figured out a way to conceal the ceramic plumbing bringing water into their city. The pipes were run in slots carved into the rock on either side of the entrance road, and the slots had then been plastered over to conceal their contents. It was the Romans who finally figured out how water was getting into Petra and this is how they came to be the first people to successfully conquer it.

The rock in the gorge (and throughout Petra) was like nothing I'd ever seen before. It was comprised of colorful sandstone, often laid down in thin beds of orange, pink, and even purple. The sandstone had been fractured by ancient earthquakes and then subsequent volcanic activity had injected molten basalt into those cracks, brazing the rock back together with criss-crossing streaks of gunmetal grey.

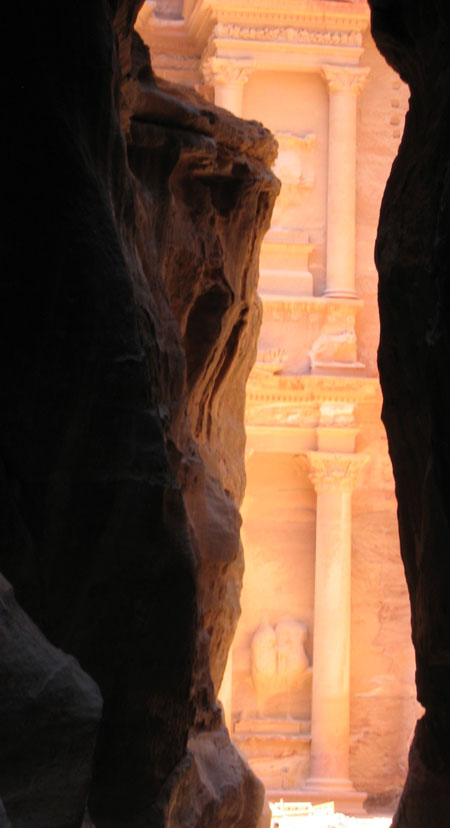

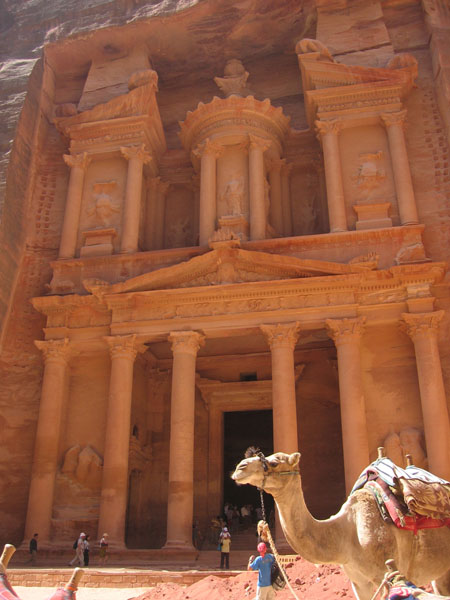

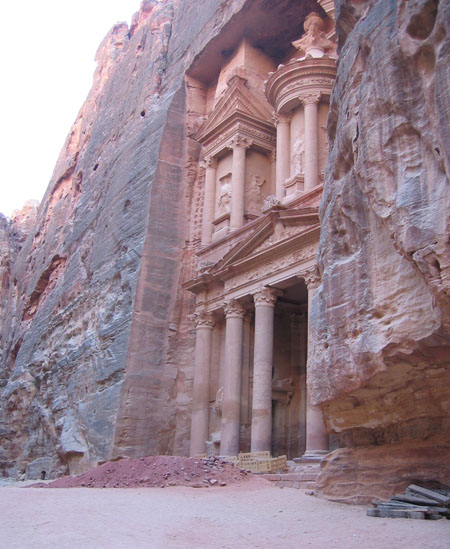

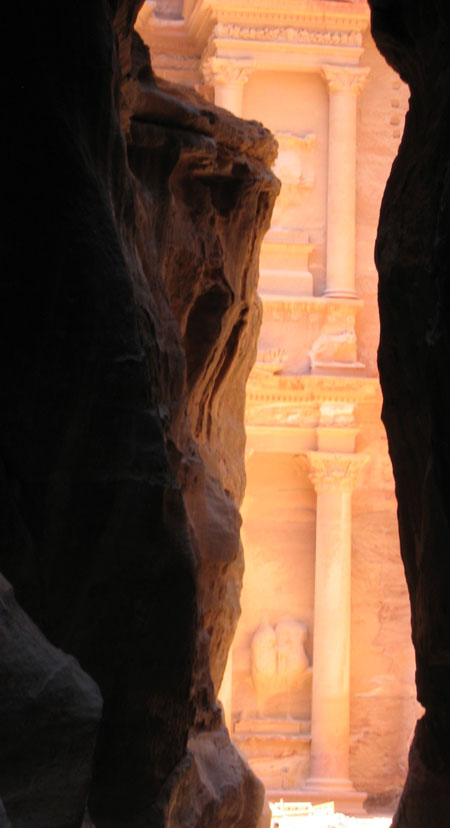

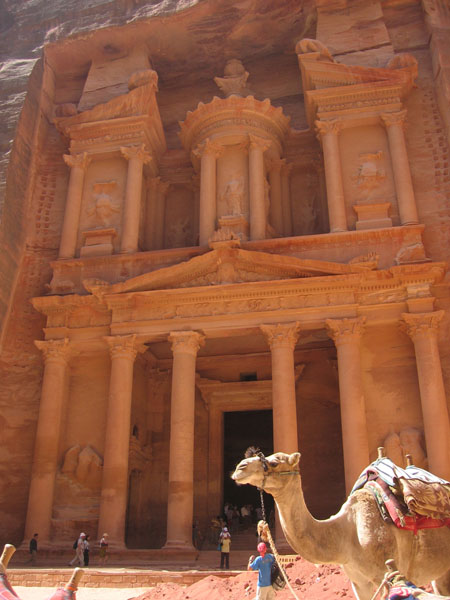

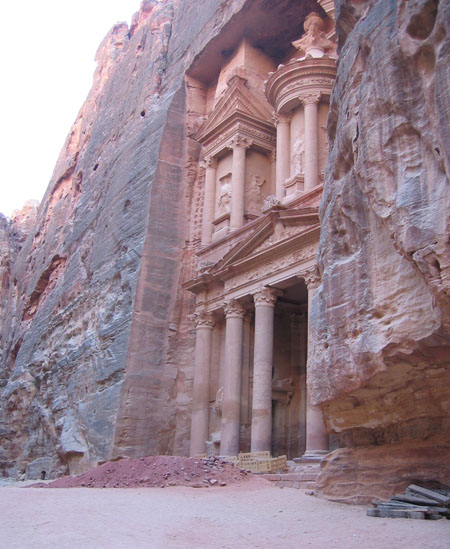

The most durable part of any lost city is its necropolis, and Petra is no exception. Coming down through the gorge, one arrives at it completely by surprise. Our guide sought to heighten the surprise by having us stand behind a bump in the wall of the gorge, walk several steps forward, and then follow his finger as it executed a 180 degree arc. And even though we knew what he was doing, wow! The first tomb is the most spectacular. It looks like a cross between a Roman temple and Brooklyn brownstone, though it was carved like a big piece of sculpture directly into the rock face. Though it started out as a tomb for a fabulously wealthy Nabatean, its details were later Romanized by Roman occupiers and it's possible it did serve for a time as a Roman temple (and perhaps, occasionally, as a residential brownstone for bands of outlaws). These days the structure is called "The Treasury" because it was once thought to contain Roman treasure. If it ever did, it's long since been taken. The Treasury has survived the sandstorms and occasional floods remarkably well, but it bears numerous small injuries from people seeking treasure. These include multiple test perforations in its façade, bullet scars in the crowning urn (which was once thought to contain unimaginable wealth), and various excavations, the latest of which are ongoing and scrupulously archæological in nature. During the height of tourist hours, a single honor guard in full regalia (including a dagger) keeps people from walking into the interior of the Treasury, though it's not as if there's anything much inside to see.

At this stage of our journey we saw our first camels and were immediately hassled by guys selling camel rides. There were also vendors selling cheap jewelry for first two dinars, then one denar, then finally a half a dinar. The proces decreased as we headed out into the wider Petra valley, whose cliffs were now crowded with monuments, some badly eroded over the course of the past two thousand years.

Such tombs required incredible expense and effort to hew into the rock, but what sort of eternity have its occupants really bought for themselves? Two thousand years later we know nothing at all about the individuals entombed except for the nature of their preferred funereal architectural. There probably wouldn't be any trace of these people at all were it not for the fact that Petra was abandoned and forgotten during the Crusader era. The eternities of people who devoted their time and treasure to writing books have had much better shelf lives.

Seeing so much real estate devoted to the dead had me wondering if the Nabateans gave much consideration to the living. But then we came to their theatre, which, though completely surrounded by tombs, once served the living.

I noticed that our guide would occasionally steer us towards certain merchants, such as the keeper of a café near the theatre (we weren't interested) or a widow with children (we bought some colorful pieces of rock that had supposedly been gathered in Petra).

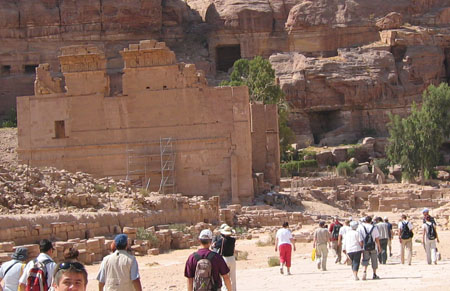

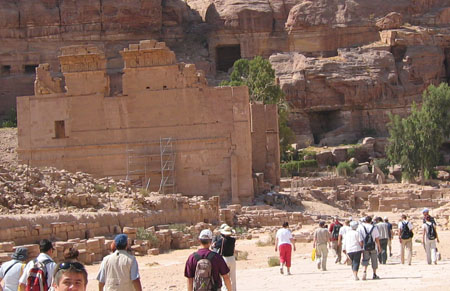

We climbed the steps to another large ornate tomb, one that had been consecrated as a church during the early Byzantine era. Then we continued into what remained of the non-Necropolis part of ancient Petra. About the only structures remaining in this area were the ruins of temples, most of which were in the midst of intense archæological activity. One one hill there was also the remnant of a Byzantine-era church whose beautiful floor mosaics had survived largely intact, probably having been protected for the past thousand years by a layer of sand and rubble.

In the center of where Petra had once stood was a modern restaurant, and it was here we stopped for lunch. If Petra were in America this would have been a dreary Sbarro franchise serving sub-mediocre food at inflated prices. But this was the Middle East, where food is important. It was provided in a spectacular buffet that was full of delicious options, many suitable for cucumber-and-eggplant-hating vegetarians like Gretchen. There was also a separate pasta bar, but Gretchen found that it wasn't so great and the sauces were "weird." While we ate, our guide retreated to the back of the dining room behind a pillar and discreetly devoured his meal, not wanting to make a spectacle of his violation of Ramadan.

After lunch, we continued to a small museum of Nabatean culture, being hassled most of the way by boys and young men who wanted to sell us donkey rides. In the museum, Gretchen's mother pointed out that a historical map of the greater Jordan area included the names and cities of all the modern countries except those of Isræl.

Walking back the way we'd come, Gretchen saw a young boy sitting on a donkey and beating it with abandon about the neck with a big stick. This was what he did when he wasn't trying to sell donkey rides. "La!" Gretchen shouted, using the Arabic word for "no." She shook her head and made a face of rebuke, hoping to at least spoil his chances of selling a donkey ride for the next minute or so. "It is not your concern," the boy replied in English.

As we continued back towards the necropolis, waves of horsemen, camel drivers, or boys with donkeys tried to sell us rides, each depending on what stage of the walk we were on. For the leg up through gorge, for example, several men tried to sell us rides in a horse-drawn carriage.

By now it was late in the afternoon and most of the tourists had already left Petra, so the competition was becoming increasingly fierce as we passed each stage of the walk to the top. This culminated at the top of the gorge where the Nabateans had built their diversion dam. This is where the horsemen offer rides up to the parking area, the reverse of the ride we'd initially taken down. They formed a human wall around us, each trying to cajole us into picking him and his horse, each offering (again) increasingly smaller prices for the service, though (as our guide made clear) we'd already paid for our horserides in both directions as part of our admission to Petra. It was so unpleasant that we decided to just forgo the whole thing and walk back to the top. And so we set off, cheerfully arm and arm, until at last we were free of the horsemen. But then Gretchen's father, who had initially expressed the most disgust with our being mobbed, shouted after us wanting to know if we wanted to ride after all. Without so many of the horsemen standing around, the horse option no longer seemed as unpleasant, so we agreed. Soon I was on a horse, being led slowly up the slope. But then the horseman jumped on behind me, and, in limited English, wanted to know if I wanted to go fast. Okay. So away we went at a gallop. It was all I could do to just stay on, but I did. We got to the top well in advance of everyone else, who were all being led by horsemen on foot. "Had I known it was going to be that way," Gretchen said, "I would have just walked." When time came to tip the horsemen, Gretchen's father gave them each a dollar, which seemed fair. But no, they didn't think it was fair. They started raising a fuss and even getting the boss horseman involved. He quickly took their side and, since he was the one who spoke the most English, words were exchanged mostly with him. His contention was that a dollar wasn't enough, but then he wouldn't specify how much was enough either. "See, this is why it's never a good idea to do anything without agreeing on the price in advance," Gretchen's father observed in disgust. Our guide was mortified with embarrassment, and he assured us that we really had paid for our rides as part of our Petra admission and that any additional money was indeed just a tip. But what do you do when a bigger tip is demanded and you think the tip was perfectly reasonable? I'll tell you what you do: you say, "Well, that was my tip. Live with it." So, after a brief consideration of the possibility of increasing the tip (But why? They're being jerks!) that was our position. The boss was now having heated words with our guide in Arabic, and it only took sentence or two before we heard the unmistakably word "Yahudi." It had only taken a minute or two for the boss's antisemitism to boil to the surface. This really pissed off Gretchen's father and he got up in the boss's face and demanded to know, "Why did you have to have to call me a Jew? Should I call you an Arab?" At this point our guide thought it best if we just leave Petra behind, and not even stop to look at any of things (such as a rooster-patterned carpet) that were for sale, since the vendors and the horsemen were all one big interwoven political entity. By now the horsemen's boss was complaining to an official Jordanian policeman and it seemed things had the potential to get even uglier. We didn't want an international incident.

As we sped away from the scene in the van, our guide explained that the horsemen selling rides (as well as the boys with mules and camels and guys with carriages) were all "Gypsies" who have a history of causing trouble at Petra. Tourism authorities try to keep things under control by paying the horsemen with a surcharge added to tour expenses, but episodes like the one we just had still happen on a regular basis. It's bad for tourism and, consequently, bad for everyone who makes money from it, including the horsemen, who still can't refrain from shitting in their own picnic basket. When our guide used the term "Gypsy," I assumed he was using the term not as a reference to the Roma people but as a general pejorative for lawless wanderers, perhaps (in this case) ruffian exiles from the Bedouin community. But when Gretchen asked where these Gypsies had come from, our guide said "Eastern Europe, mostly." He really had meant Roma when he said Gypsy. "Did you see how they are darker than Jordanians?" he asked us. "This is because they are not from here. They come here and they cause trouble."

For the rest of the afternoon our guide was profuse in his apologies, making repeated assurances that the Gypsies were not representative of the Jordanian people. His mortification was understandable; in just one comment the horsemen's boss had undid all of our guide's careful bridge building and cast doubt on the appealing picture he'd painted of Jordanian tolerance and modernity.

Seeking to redeem some of this picture, our guide took us to a market in modern Petra. We walked around looking at piles of fruits and vegetables and tasting free samples. One of the shop owners (whose sign featured a picture of his face in front of the Treasury in ancient Petra) gave us a whole pomegranate to eat. As we did so, I noticed another shopkeeper at an adjacent booth. He had his his forehead resting wearily on the palm of his hand as he measured something out with a scale. It was late in the day and clearly the Ramadan fast was getting to him. Like everyone else we'd met, he probably knew to the minute how much time remained before he could eat again.

Before returning us to our hotel, our guide took us to the highest part of Tybet so we could look down and see the city and surrounding countryside. We were quickly joined by couple curious village boys, one was maybe four and the other eight years old. They stood around looking at us intently as we chatted. Eventually our guide called the younger the boys over, patted him on the head, and gave him some pocket change, telling him to share it with his brother. The little boy was delighted and immediately went to his brother and offered him some coins. But the older boy refused them in what I initially took to be a show of financial transcendence. Only later did he make it clear what his game was. As we were leaving, the older boy tagged behind me a pace or two and quietly begged "One dinar!" This magic English incantation had probably worked in the past, but after a day of hearing it repeated over and over it seemed tawdry to me. One dinar for what, exactly? "No!" I said in exasperated English.

The road down the narrow gorge leading into the Petra necropolis.

Remnants of the original crypto-aqueduct into Petra. These channels once contained ceramic pipes that had been hidden behind a wall of mortar.

Basalt-filled cracks in Petra sandstone.

The gorge road.

An ecumenical pantheon along the entrance gorge road.

Gretchen poses with some colorful rock along the entrance gorge road.

First view of the Treasury from the entrance gorge road.

The Treasury.

The Treasury later in the day, at a different angle.

Gretchen with the Treasury's Jordanian honor guard.

A Nabatean shrine.

Faint remnants of the tomb façade on a cliff face.

The Petra theatre.

A swath of Necropolis.

The same swath, later in the day.

The Urn Tomb.

Looking out from inside the Urn Tomb.

A Bedouin widow and children in traditional attire.

An international collection of footprints in the sand.

The only intact free-standing structure in Petra, the remains of a temple.

Donkeymen near the museum.

A harpy in the Petra museum.

Chicken mosaic on the floor of the Byzantine church.

Dolphin mosaic on the floor of the Byzantine church.

Signage and bananas in the market in modern Petra. Note the shopkeeper's picture taken in front of the Treasury.

For linking purposes this article's URL is:

http://asecular.com/blog.php?051006 feedback

previous | next |