|

|

|

rookeries of North Seymour

Friday, January 28 2005

setting: Black Turtle Cove, Santa Cruz Island, Galapagos, Ecuador

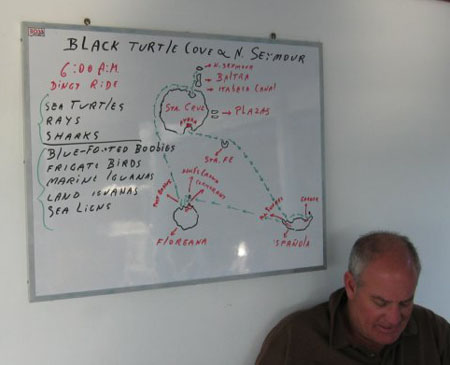

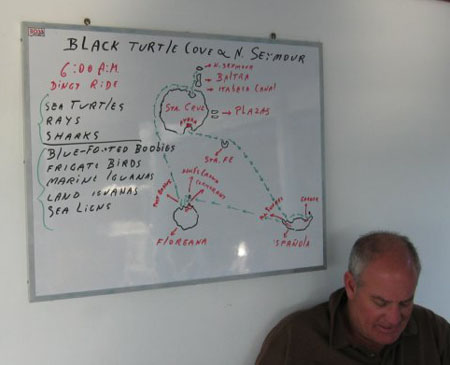

Through the night we sailed north from Floreana back to the island of Santa Cruz, ending up on its north shore in place called Black Turtle Cove. Superficially, the cove looks lush due to its thick blanket of mangrove vegetation. But if you look through the little mangrove trunks you can see for yourself that there's almost nothing there but rough lava boulders and mangroves. There's virtually no soil whatsoever and no vegetation besides the mangroves themselves.

After breakfast we all went on a panga ride to see the wildlife that calls this cove home. Our first destination was on the east end of the cove, a region of especially calm waters preferred by sea turtles for mating. The mangroves themselves seemed to dictate how far back into the maze our panga could go. Some avenues were so choked that we could barely get through in our humble little punk rock dinghy. This was good because it meant we could get into places unreachable by all the elderly American tourists being ferried around on big fancy inflatable Zodiacs.

After a little time spent trying to be patient, we began seeing the turtles. First we saw them swimming solo, big ghostly forms in the clear still water. But then we'd see them together. Most of them were there looking for love, and after awhile the only ones we saw were in the process of mating. For sea turtles it's an exhausting two hour ordeal, with the female controlling when everyone gets to breathe. It's apparently a fairly oxygen-demanding activity, since mating turtles spend an unusual amount of time with their heads above the surface. But there's plenty of diving and swimming around beneath to keep things exciting. As we were leaving the grove we encountered a turtle menage-a-trois: three turtles riding in a piggyback-on-piggyback formation. I don't know what if anything this meant for the paternity of their children, but if it violated God's laws He wasn't exactly sending a tempest to stop it.

After we'd toured the east side of the cove we went looking for sharks further west. Amazingly, though the scenery didn't really change, the turtles mostly disappeared and were replaced by sharks. Generally they took the form of spooky six-foot-long forms moving silently beneath the water, though the water was so clear that sometimes you could read the matter-of-factly determined expressions on their faces. These were White-Tip Sharks, so named because the tips of their fins are each colored with a dab of white. Generally they swim too far beneath the surface for their fins to ever cut the surface (the way you're probably imagining that they would).

Further into the cove we encountered what can only be described as a flock of Spotted Rays serenely flapping past.

Since the beginning of the Ecuador trip I'd been having trouble with my technology. I'd brought my Apple iBook, hoping to use it as a repository for digital photos so my camera's memory card would always have plenty of room. But at some point I'd discovered that the iBook wasn't recognizing my CF card reader. It was still good to have the iBook for writing and reading saved articles, but I really wanted to be able to work with my pictures too. I'd been mentioning this problem to others on the boat in hopes that they might have brought a CF card reader or a USB cable. Finally today I mentioned it to the right person. She was Karin, one of the three Swedish women on the boat. Her camera accepted CF cards and she just happened to have her USB cable with her camera. Best of all, when she plugged her camera into my iBook, the CF card mounted on its desktop just like another hard drive. So we decided to act like organisms in a symbiotic relationship and help one another out. I would download my pictures to my computer, she would download her pictures to my computer, and then we'd both clear our memory cards. This would be possible because I promised to burn her a CD of her pictures and mail it to her once I returned to the United States (after, of course, pausing first to remember the terrible events of 9-11).

In the afternoon the Golondrina motored to the port in Baltra, the island with the airport where we'd first touched down in the Galapagos. Today was to be a resupply day. The Golondrina would be refueling, resupplying its food and water stores, and throwing out garbage. We'd also be unloading some passengers and taking on new ones. Happily, the ones we'd be shedding included the most obnoxious of the Australians and the German guy, the one who has suffered so much at the hands of the Jews.

The plan was for Golondrina's remaining passengers to leave the boat and hang out on the dismal Baltra beach while all this was going on. Supposedly there's some sort of Ecuadorian law requiring that the passengers be offloaded while a boat is being refueled. But the Golondrina crew didn't care if we stayed on the boat so long as we kept inside.

In the end we only took on one new passenger, an extremely unattractive German woman who could speak some English and somewhat less Spanish. Later on while she was snorkling I saw how her pubic hair was struggling out of her bathing suit and it sent shivers down my spine.

After we were done with our business in Baltra, the Golondrina set a course for the next minor island a short ways to the north, North Seymour. Here we had a dry landing and went on a walk through frigate bird and Blue Footed Booby rookeries, encountering numerous giant land iguanas along the way. There was also a stretch of rocky shoreline being slammed by the waves, and there were a good many sea lions sunning themselves there.

The most unexpectedly bizarre of all the creatures on North Seymour were the frigate birds. It wasn't just that the males have a huge red sack in their throats that they inflate to attract females (I'd seen that in books). It was a creepier thing, the fecundity in the face of death, that most affected me. Frigate birds have the greatest wingspan-to-bodyweight ratio of any bird, and it seems they can easily get their long wings entangled in vegetation. If they prove unable to extricate themselves they starve to death and mummify. Most of these mummified frigate birds are found in close proximity to active nests in the frigate bird rookeries, since it's during the feeding of the young that the birds are most likely to get their wings caught in the shrubbery.

North Seymour was the place where we could finally get good pictures of Blue Footed Boobies. They were utterly indifferent to us or the works of our species, choosing in some cases to locate their nests in the center of what is a heavily-traveled path. Most of the boobies were still in the courtship stage of their relationship with other boobies. You could tell which ones were the males because for some reason dilated pupils are a male booby trait.

For the night the Golondrina pulled in close to the sheltering cliffs of Baltra island. It was a good place to watch the sun setting far off beyond the Daphne islands, somewhere on the sleeping mass of the Galapagos' biggest island, Isabella.

The Golondrina's whiteboard this morning, with the quietest of our Australians.

Sea turtles getting busy in Black Turtle Cove.

Spotted Rays in Black Turtle Cove, Santa Cruz Island.

A land iguana on North Seymour. These iguanas were actually introduced by American troops to North Seymour in the 1940s from Baltra just before the Baltra iguanas went extinct.

Land iguanas mostly eat cactus.

A creepy knot of marine iguanas on North Seymour.

A Blue Footed Booby set against Daphne Minor.

Figate birds in a North Seymour rookery.

A male frigate bird with his silly red pouch on North Seymour.

Sunset illuminates shrubby trees atop the Baltra cliffs.

For linking purposes this article's URL is:

http://asecular.com/blog.php?050128 feedback

previous | next |