|

|

|

chicken buses of Guatemala

Sunday, March 12 2006

setting: San Marcos La Laguna, Lake Atitlan, Guatemala

It was a beautiful sunny morning in San Marcos La Laguna, and when the fog eventually burned off we could see the perfection of the nearby volcanos in all their conical glory. We walked to a restaurant called Tul Y Sol, which had a veranda view of the lake and the volcanos, and there I ordered my first coffee in many hours. I was in the height of caffeine withdrawal at the time and this one cup made me feel as if I could calmly and benignly rule the planet from where I was sitting. The restaurant didn't have any tofu, though they somehow made me the best grilled cheese sandwich I'd ever eaten. The not-so-secret incredient was onions.

After breakfast we waded out into the lake a short distance and I took the time to correct a shoreline danger, a board with rusty nails pointed skyward. I have a feeling that most of the sewage from the lakeside villages finds its way into the lake untreated, though it's deep and contains so much water that it seems to completely absorb its many insults.

Gretchen had a little extra food from her breakfast, and she gave it to one of the now-familiar street dogs of San Marcos La Laguna. The wild dogs in the village look reasonably healthy and there aren't all that many of them. They keep to small territories and interact pleasantly with the handful of off-leash pet dogs also there. But earlier this morning, Gretchen had climbed up out of the village to a roadway and found a more typically Third World Latin American site: a mixture of dust, concrete, rebar, and trash, with a heavy sprinkling of skinny, listless street dogs. In the Middle East, the ubiquitous feral animal is the housecat (evidently wild dogs are not tolerated there). In Latin America, though, dogs are everywhere. There are so many that one doesn't normally see any cats. In Latin America, the cats that don't get eaten live most of their lives on rooftops.

After we checked out of our hotel we realized we didn't have sufficient quetzales to afford a boat ride back to Panajachel, and none of the stores were willing to change American dollars for us. We were stuck; it's not like there are any actual banks in a village of this size. In the end, though, we went back to our hotel and Gretchen got the woman there to change money for us.

On the crowded boat back to Panajachel we found ourselves talking mostly to a pair of women from Austin, Texas. They pointed out a few buildings that still lay on their sides in the aftermath of Hurricane Stan.

For most people in Guatemala, transportation between cities and towns is done in "chicken buses." These are old American school buses (all of them made by Blue Bird East, the manufacturer of the buses I rode in as a kid). Most of these have been repainted in festive colors and lavishly decorated, especially near the front, usually with religious iconography. Whatever pollution controls the buses might have once had have all been removed, and they're famous for the noxious clouds they leave in their wakes as they chug up steep mountain roads.

Gretchen and I caught one such chicken bus to begin our ride from Panajachel to our next destination, the city of Quetzaltenango (known mostly as "Xela," pronounced "shay-luh"). Soon after we climbed in, it became clear we were surrounded by other gringos. But these weren't your usual gringos; they were all speaking to each other in Spanish. It turned out that they had already been in Guatemala for weeks doing what we'd just come to do: learning Spanish. Language immersion is difficult when you're surrounded by your own countrymen, so they were imperfectly maintaining their immersion by choosing to communicate with each other mostly in the language they'd come to learn. Their Spanish was much better than mine and already I felt like I was way, way behind. That wasn't my only disadvantage. As always, Gretchen had planned all the details of our trip, and I hadn't bothered to learn what language school we were going to or even that "Xela" was the informal name of Quetzaltenango, so when the other students talked to me about these things, I mistook such proper nouns for unknown Spanish vocabulary. It was both humiliating and exhausting at the same time.

Nevertheless, Spanish wasn't proving to be quite the alien language it had once been. I found myself having a reasonably good understanding of overheard conversation, particularly between one of the local Guatemalans (he was studying to be a doctor) and one of the gringos in our contingent.

It was a great and wonderful coincidence that nearly all of the students on our bus were attending Celas Maya, the same language school Gretchen and I would be attending. This greatly simplified things when we picked our way through Xela from the chicken bus to the school.

Xela is a grim, grimy city perched 7743 ft above sea level. Like Quito (in Ecuador), it suffers from the problem that comes when thin air is mixed with abundant air pollution. By contrast, Celas Maya is a little enclave of greenery and respite form clouds of deisel fumes. It's centered around a garden courtyard, though it also features a kitchen with a bottomless coffee supply, a computer lab for connections to the rest of the world. Soon after arriving, we were picked up by Lily, the 60-something-year-old woman who would be serving as our "mother" for the next two weeks. The way these language schools work is that they set up their students with a nearby family, which provides an immersive language environment as well as regular meals and a bed to sleep in. Lily's house was 10 or 12 blocks away, a grim concrete-faced "townhouse" separated from the rushing, belching traffic of Avenida 20 by a narrow 18-inch-wide sidewalk (a typical sidewalk width in this city). Our room was upstairs and featured lots of bad pictures of pet animals (some of them Garfield) on the wall. Lily actually had two rooms for student guests, but she'd only be needing one of them for us, since we're a properly married couple. Despite this, though, for some reason she insisted on keeping that extra student room vacant, even though it meant that she and her granddaughter had to sleep in the same bed in the house's only non-student bedroom. In addition to Lily and her granddaughter, Mario (one of Lily's sons) lived in a makeshift "room" out on the back porch above a tiny courtyard.

Volcanos in the distance above Lake Atitlan.

Once the haze lifted, the volcanos were clear.

A street dog on the dock in San Marcos La Laguna.

Gretchen cuddles a street dog while a pet dog behind her looks on.

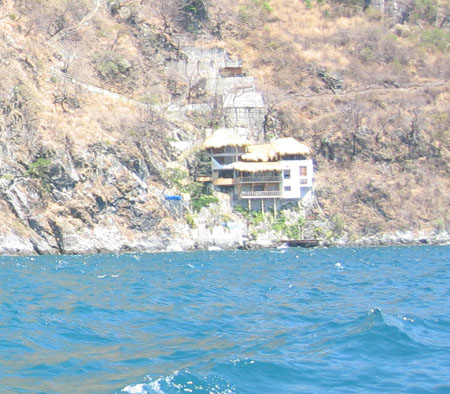

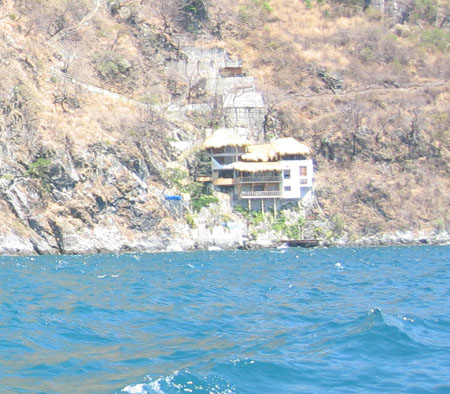

One of the many compounds on the coast of Lake Atitlan.

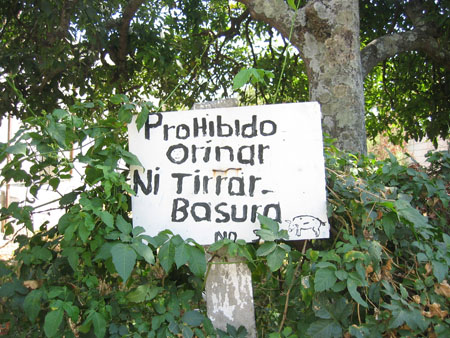

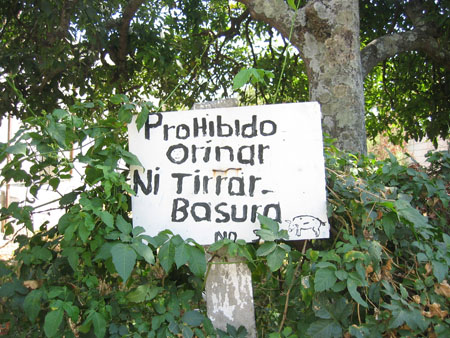

A sign in Panajachel. The last line reads "No sea [picture of a pig]."

For linking purposes this article's URL is:

http://asecular.com/blog.php?060312 feedback

previous | next |